Onyx Odyssey

2015-2016

HYDE PARK ART CENTER

Onyx Odyssey is a journey into blackness and all its complexities as navigated by artist Jefferson Pinder. On a literal level, blackness is a color property experienced through sight resulting from the absence of light, prompting the inability to see. In cultural discourse, blackness is a state of being constructed by an exponential variety of experiences that make up a person’s character in relation to the color of his or her skin. Scholar Rone Shavers explains “’blackness’ is a specific set of cultural and social tropes that mark and define an ethnic or racial identity and implies a shared notion of historical, social, and cultural traditions.”1 Both the scientific and the socially-constructed definitions of blackness inform the hauntingly mysterious and powerful work of interdisciplinary artist Jefferson Pinder.

The exhibition Onyx Odyssey presents Pinder’s recent explorations on the topic of being black that reconsider clichés of blackness to illuminate the perpetual and vibrant shifts of black identity spanning the trajectory of time. Emerging onto the contemporary art scene during the “post-black” moment at the turn of this century, Pinder’s artwork stands out for its material directness and heightened sense of physicality to addressthe limitations, ironies, and contradictions in historical representations of blackness in America. Rather than use humor as a strategy that diffuses racial tension, he heightens tension to create a dynamic experience for the viewer. His knowledge of performance comes from formal training in theater, which charges his sculptures, paintings, prints, and installations with spectacular intensity. Playwrights and writers Amiri Baraka, August Wilson, and Ralph Ellison, to name a few, greatly influenced the development of his creative voice. Their ability to awaken society to systemic racial injustice and connect to the individual on a human level reveals an honesty that Pinder achieves through his commitment toward the black male body in his performances and art objects.

The black male experience is central to understanding Pinder’s work. His interpretation of blackness revitalizes the discourse of the gendered, racial body presented in the Whitney Museum’s groundbreaking exhibition Black Male (1994). Curator Thelma Golden wrote, “One of the greatest inventions of the twentieth century is the African-American male—‘invented’ because black masculinity represents an amalgam of fears and projections in the American psyche which rarely conveys or contains the trope of truth about the black male’s existence.”2 Pinder’s study of the black male builds on Golden’s realizations and further complicates the notion of invention by referencing a selection of black figureheads from The Reconstruction and Civil Rights Era to the Black Power and Black Lives Matter movements. Through Pinder’s work we are reminded that the black man has always reinvented himself by performing blackness—in 40 million ways, according to Henry Louis Gates Jr.—as a way of addressing the alienation of time and place. This displacement is expressed in Pinder’s work through the intergalactic imagery spread throughout the exhibition.

Onyx Odyssey includes several works that directly reference historic black figures such as WEB Du Bois, Huey P. Newton, Sir Moriaen, and Barack Obama. The video work Overture grounds the exhibition with Pinder’s non-linear adaptation of Du Bois’s history play The Star of Ethiopia, as discussed by Amy Mooney. Unlike Du Bois’s celebratory, epic production, Pinder’s short video is eerie, modest, and subtly fierce. Containing untrained actors cast from the streets of Chicago, the piece projects the mythic “mother of men” floating through the desolate streets of West Loop / Garfield Park as if to assess the current condition of contemporary black community. Equally as foreboding, the set of three monoprints included in the show contain a floating skull layered atop the popular revolutionary image of Black Panther co-founder Huey P. Newton enthroned and armed with guns. Newton presents a tragic black hero that began with an ambitious militant plan to ensure the rise of Black Americans. Decades after Eldridge Cleaver made this iconic photograph, Newton was murdered outside of a drug den, allegedly buying drugs and playing out the stereotype of the Black man living in the Reagan era.

A lesser-known soldier is the namesake of Pinder’s installation Moriaen’s Shadow, featuring an original sound work that emerges from thirteen metallic organ pipes in various heights and patinas standing upright in a loose diamond formation. Sir Moriaen, the only Black Knight of the Round Table (c. 13th Century), fought Sir Lancelot while on a quest to find his father and legitimize his bloodline. Considering this connection, the pipes appear like armor for strange knights with pitched hats that seem both alien and reminiscent of the Ku Klux Klan. This sensation is heightened by the unsettling combination of sounds: fire crackling and horse hooves hitting the ground mixed with episodes of choral music and triumphant orchestral riffs sampled from science fiction movies. Each of the men Pinder references in these art works perform acts of resistance in a variety of ways and draw renewed attention to their distant narratives that he then intertwines in Onyx Odyssey.

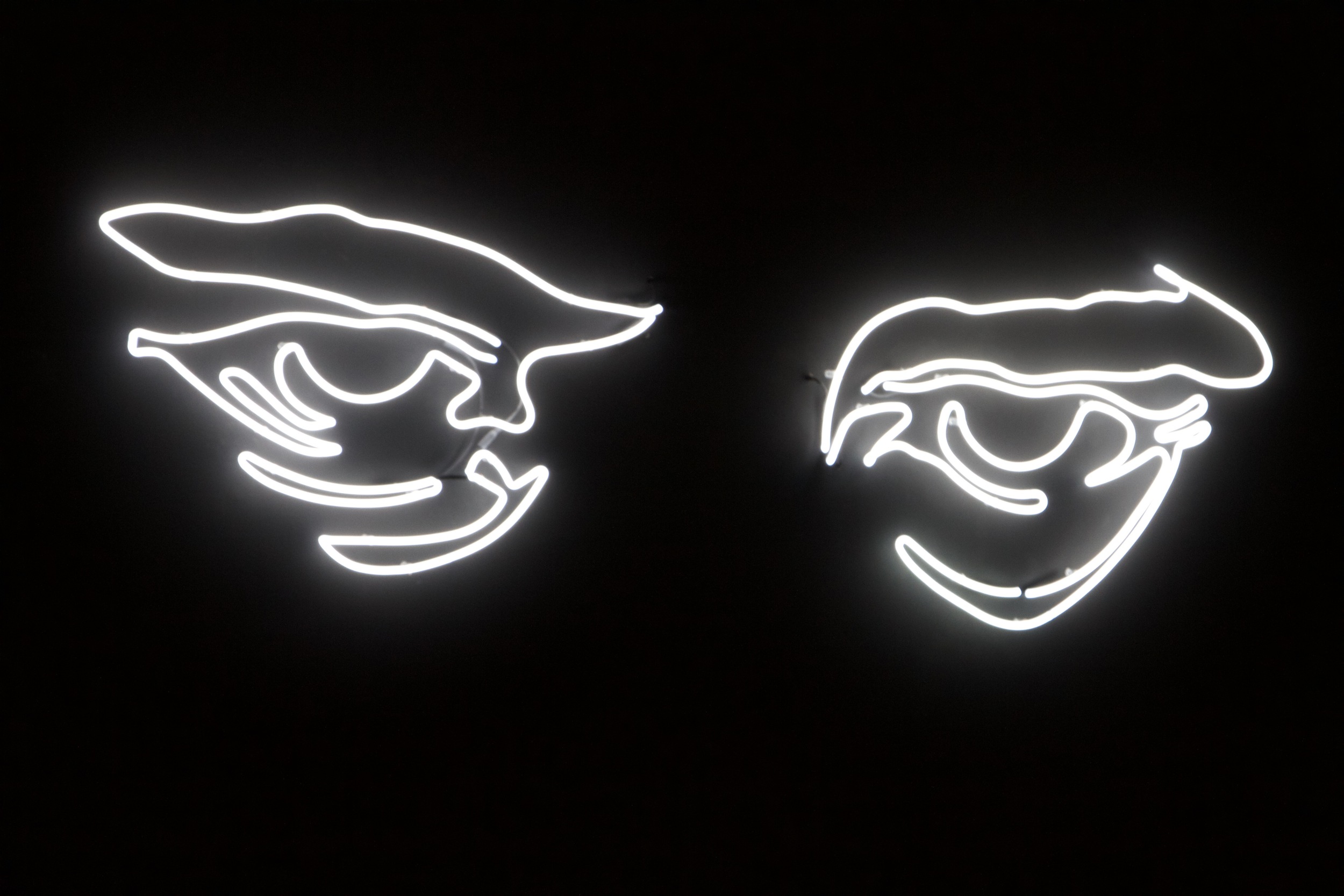

Barack Obama is the only living black man referenced directly in this new body of work by Jefferson Pinder debuted in the exhibition: a large white neon installation hovering above the gallery on a black wall. Newly commissioned by Hyde Park Art Center, POTUS (acronym for President of The United States) is a line-drawn depiction of Obama’s “angry eyes,” which is a memorable expression Pinder encountered in a news photograph. The stern and tired glare suggests underlying dissatisfaction with us—the citizens— who traverse his gaze on the gallery floor. The leader of the free world has a strong presence in the show as a significant and contradictory figure of black power in America. In opposition to the president’s Big-Brother-like gaze, the site-specific digital video Countermeasure presented on the Jackman Goldwasser Catwalk Gallery was inspired by the recent waves of protest associated with the Black Lives Matter movement. Presented in cool blue tones, the large-scale silent work features the breakdance crew Lionz of Zion interpreting gestures of riot. Wearing the current urban uniform of resistance— hoodies and jeans—these b-boys demonstrate extreme mastery over their body’s movements, precise pauses, and contortions as if they are fighting off an invisible perpetrator amid the smoky darkness. Bandanas tied around their faces negate racial profiling, while indicating there is terror and violence to come.

Endurance is a reoccurring theme in Pinder’s work, as is (in)visibility of the body through sound and light. New work in the exhibition, previously mentioned and including Monolith and Gauntlet, show direct signs of containment in Pinder’s work and raise questions concerning how one moves within set social boundaries and controls. Perhaps that is the odyssey: a meandering adventure of epic duration to reorder the external influences that shape oneself while eluding restrictions based on color and gender. For artist Jefferson Pinder, the journey provides a metaphor for the Black American experience and raises questions about the history, myth, and meaning of blackness that construct a fraught racial identity that has carried into the 21st Century.

Written by:

ALLISON PETERS QUINN is the Director of Exhibition & Residency Programs at Hyde Park Art Center, where she has curated exhibitions and produced symposia, performances and publications since 2004. Her writing has appeared in Proximity Magazine, Service Media: Is it “Public Art” or is it art in public space? and artists’ monographic publications including Susan Giles: Scenic Overlook (2015), Cándida Alvarez: mambomountain (2013), and William Steiger: Transport (2011).

1 Shavers, Rone 2015. “Fear of a Performative Planet: Troubling the Concept of “Post Blackness.” In The Trouble With Post-Blackness, eds. Houston A. Baker and K. Merinda Simmons, 82. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

2 Golden, Thelma. 1994. Black Male: Representations of Masculinity in Contemporary AmericanArt. New York: The Whitney Museum of American Art; 19.